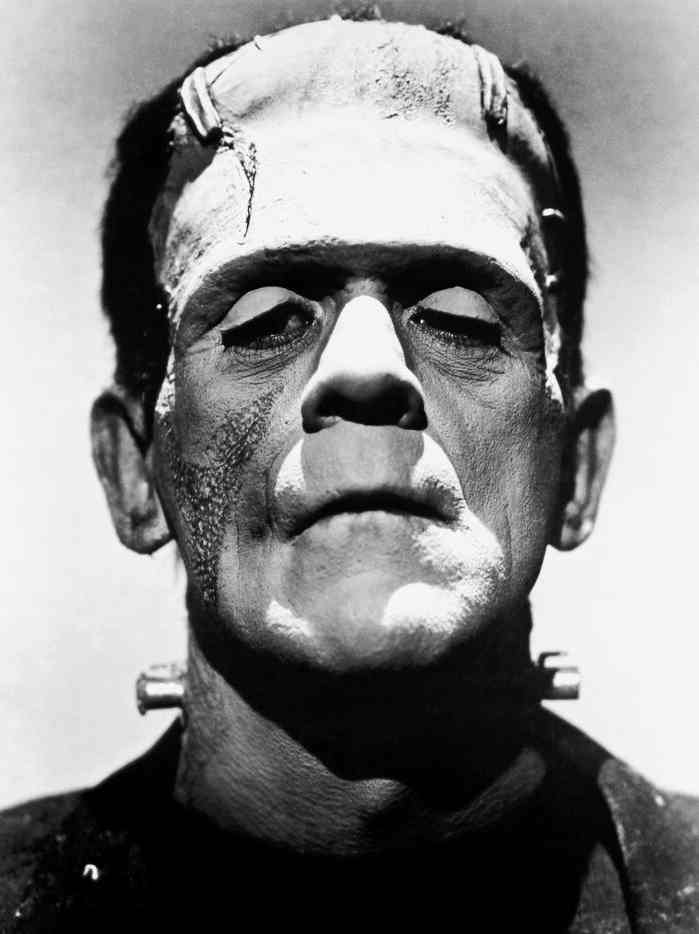

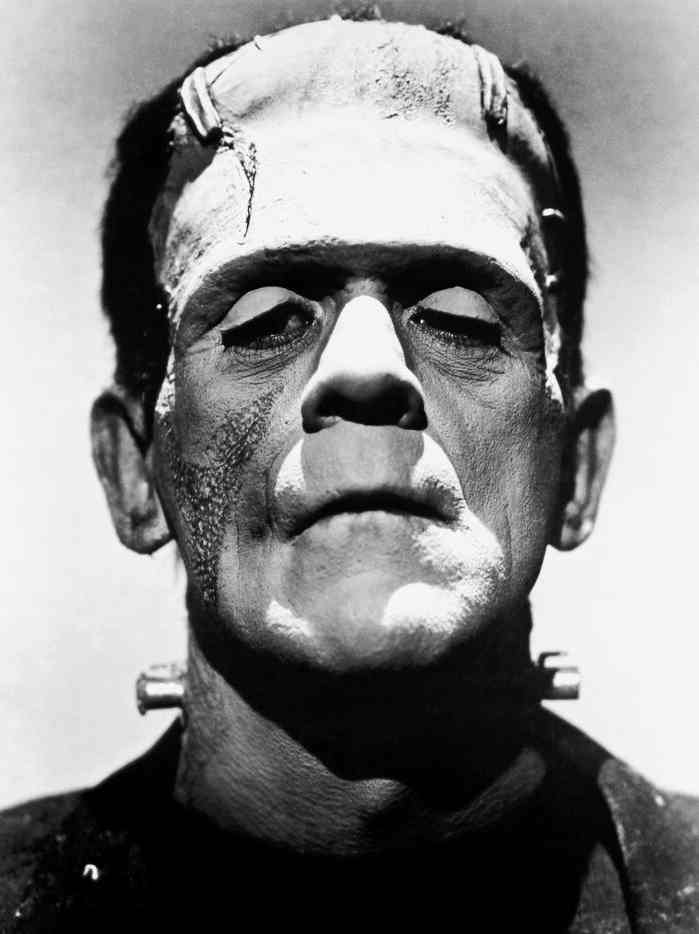

Let me just preface this post by saying I was raised on the classic Universal horror films, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolfman, etc. Frankenstein especially was one which stuck with me over time, perhaps because I saw basically every single Frankenstein movie made in black and white. I mean, we're talking Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, Son of Frankenstein, Ghost of Frankenstein, Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman, even Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Despite the fact that the last time I watched most of these films I was probably nine years old I still remember them and I have in my mind a clear idea of what the Frankenstein story is and what it entails.

Imagine my surprise when, in high school, I was talking to an upperclassman friend of mine who was reading Frankenstein and discovered that practically everything I considered to be Frankenstein was absent from the novel. No creepy labs full of Tesla coils on stormy nights wherein a wild-eyed scientist and his hunch-backed assistant bring forth a monstrous creature with an abnormal brain, no Transylvanian castles and townspeople with pitchforks, no burning windmill. I mean the monster isn't even terrified of fire for Heaven's sake, and he can talk. In fact, not only can he talk, he is fluent in a couple of different languages. Needless to say my entire childhood concept of Frankenstein was very much rocked that day.

I did not actually read the novel until the last week of winter break, I simply knew second hand of some of the differences from what I had overheard from people who had read the novel. So I guess the shock of the differences which I found in the text was cushioned by prior knowledge of a few of them. This is a common problem for me, I tend to find out twist endings of films before I watch them and video games before I play them so I'm adjusted to going into things knowing what happens. Regardless of that prior knowledge I was completely unprepared for Victor and my huge distaste for him. I can understand to an extent his reactions after creating the monster, becoming physically ill with the guilt and horror of his actions, but the reasoning behind his reanimation of dead flesh irritated me. This is a man who has literally everything, loving family, means to do what he wishes with his life, supportive friends and a generally pleasant upbringing. He went out to create the creature just because he could, he didn't think about the possible ramifications of his actions, how his creation might destroy his life. He simply pursued the selfish goal of seeing if he could accomplish what no one before had done, and it was the hubris of his actions that led to his downfall.

Hubris is a common theme throughout horror, some person who thinks that they can do anything and everything to no ill effects ends up creating something which becomes their downfall and usually takes out quite a few of their loved ones along the way. So it is with Frankenstein, starting with the creature killing Victor's youngest brother and culminating in the murder of Victor's new bride, yet at any point, even after creating the creature, the killings could have been prevented. The monster simply suffers from a lack of love or affection. He is too hideous for anyone, even the man who created him, to look upon, and so his loneliness fuels a homicidal rage towards the creator whom he blames for everything that has gone wrong in his short existence. Yet even after the murder of Victor's brother he could have simply created the partner for his creation and prevented the murders of his best friend and his wife. But he doesn't. He gets all the way to that threshold and stops. Why?

That is a question to which I have no answer. To my mind the creation of the bride might have a least sated the creature and made him less lonely, but I can understand Victor's fear of having two giant undead creatures roaming the Earth. Still, for all his intelligence, I find Victor to be an idiot, a selfish fool who cannot solve his own problems and thus creates his own death. There is no neat romantic ending to this and there is no real Gothic heroin, merely a fool of a man trying to play God and thus destroying everything he holds dear.

Satire is one of my favorite genres just in general, and Terry Pratchett and Douglas Adams are two of my favorite satirical authors because they mock fantasy and sci-fi, and as sci-fi is the current topic of discussion in our class Douglas Adams is the one upon whom I will focus.

Satire is one of my favorite genres just in general, and Terry Pratchett and Douglas Adams are two of my favorite satirical authors because they mock fantasy and sci-fi, and as sci-fi is the current topic of discussion in our class Douglas Adams is the one upon whom I will focus.